A rural landscape in mid-Wales, where the reintroduction of pine martens is actively taking place. (Peter Cooper)

Memories are fickle old things. They are the sum of who we are as people. Our best days and worst days, while long gone physically, can stay with us for life and define who we are. They can even be shared between generations, and shape our reality. Yet as those generations pass, those memories become stories. And if they are not documented scientifically, they can blur the lines between fiction and reality.

Here in the UK, our own generational memories of the countryside often determine what we prioritise in wildlife conservation. The trouble with this is that with each successive generation leaving less nature behind than the one before it, our perception of what is healthy becomes skewed over time. It can pre-determine what we value; much attention is currently being given to curlew recovery, with older folk still remembering a time when they were common on farmland. But the once equally numerous corncrake receives nowhere near the same attention, perhaps because the witnesses to its former abundance have effectively died off.

This is the shifting baseline syndrome. The presumption that what we grew up with is the norm. Needless to say this has been written about numerous times but, in short, it is a barrier that can restrict us from realising the fullest possible ecosystem. And one doesn’t have to go far to find written sources that make us realise what we have lost.

Among the more ‘recent’ accounts are local bird atlases. Ever since a few eccentric Victorians decided that maybe admiration was better respected by observing and recording the birds they saw rather than blasting them out of the sky, the hobby of birdwatching gives us a diary of shifting fortunes.

Take for example the bird records of my motherland, Hampshire. I now own two of the county’s bird atlases, one being the most recent, published 2015 and covering 2007-2012. The other is a far older tome from 1963, covering much of the 1940s and 50s. I’d found it in a second-hand bookshop in Winchester I used to frequent back when I was a sixth-form student, and the musty aroma of ‘ancient’ knowledge was too enticing to just leave it on the shelf. But putting one by the other, the differences are pretty stark.

There are some success stories. In reflection of their national status, buzzards and sparrowhawks go on to fill more or less every survey grid in the 2015 atlas, compared to the 60s edition where you were looking at a couple of pairs of each left in the New Forest. Likewise, many wetland specialist birds, like bittern and egret, are returning in higher numbers today. But much of it is tragic. Lament the extreme declines in birds like curlew, corn bunting and stone curlew in 50 years, or in the case of the cirl bunting, black grouse and corncrake (them again), complete local extinction.

The Black Cock Inn on the edge of Exmoor, Devon. No doubt named after birds that were once local in the area until the early 20th century (Photo: Pete Cooper)

While we have detailed bird records from the last couple of centuries, species with particular cultural significance can be traced back even further. Moving across to where I lived as a student, the expansive History of Cornish Birding takes a TARDIS back to medieval times with two species that were numerous and charismatic enough to warrant extensive mention then; the chough and puffin.

Nowadays, choughs are at least recolonizing Cornwall steadily from the Lizard and Land’s End. Yet before then, they held the honour of being the Cornish bird, even though they were common all the way to Kent. Despite being honoured on local heraldry, persecution and habitat loss pushed them towards extinction as breeding birds by the 20th century.

The puffin was even more unfortunate. This was once such a numerous breeding bird on the Cornish coast that tenants, like something out of a Monty Python sketch, exchanged dead ones as rent. Undoubtedly the mass overfishing of species like pilchards led to the puffin’s local demise to just a few pairs near Tintagel, which disappeared by the 1960s – and I suspect that poor, hungry folk prior to then helped clean up what was left. (Incidentally, the demise of chough and puffin is also recorded in the 1963 Hampshire Atlas – both species were once common on the Isle of Wight)

But most of our pre 20th century records come not from a place of respect. They come from hit lists. This is probably best exemplified by old bounties from rural parishes, where these had to be maintained by law after Henry VIII introduced the ‘Act for the Preservation of Grain’ (which Elizabeth I enhanced further in 1566).

You can read and weep at the efficiency of this act in the incredible book Silent Fields, by Roger Lovegrove. Published 10 years ago, I finally came across it myself last year. I soon discovered I had found both a treasure trove of information even richer than the bird atlases – and a tragic tome that almost read like a eulogy.

After unsettling you with the tales of how early on we got rid of our large carnivores (bears, wolves, lynx) and most large herbivores (moose, aurochs, beavers and boar) and systematically ensured most of our woodlands and wetlands disappeared, the book goes into great detail on the animals that fell victim to the vermin acts.

Companions you’d be hard pressed to find a grudge against today joined many of the usual suspects on the wanted list. Alongside the fox and badger, crow and buzzard, were bullfinches and water voles, dippers and kingfishers, all with prices on their heads. In the eyes of the exterminator they were nothing more than plagues upon fruit blossoms, the roots of crops and the fry of prize fish.

The ferocity of the killing is shocking in many cases, and that’s just on the records that Lovegrove was able to collate, or were directed to the churchwardens in the first place. The parish of Sherborne in Dorset for example saw 1,940 stoats, 3,344 hedgehogs and 8,379 sparrows slaughtered between 1662 and 1799. On a widespread scale, this co-ordinated massacre hammered populations of many species to way below what they should be.

Notably, species that we now associate with wild Scottish places were widespread across England and Wales, and it’s here that the filter of our shifting baseline becomes clear. Ospreys, golden and white-tailed eagles were wiped out across these places early on in the Act’s life, with only a few dwindling populations left to eke out existences afterwards (back to the Isle of Wight again – the last English white-tailed eagle pair were said to have nested there on Culver Cliff in the 1890s). Pine martens and wildcats were numerous right up until the 18/19th centuries, where the records show them hanging on in Wales and the West Country. And polecats and red kites, although now rebuilding their former ranges, were two of the most common predators out there.

Such was the slaughter that we learnt to accept the wild and windy regions of the country as the natural retreat of eagles, martens, wildcats and others, sanctuaries that became even scarcer with the rise of the shooting estate in the 19th century. Each successive generation became convinced that it was the natural order, and not just for the more charismatic species.

There have always been those who question the plummeting diversity and abundance of bird and insect life as farming has become startlingly more intensive in a manner of decades. An excellent article from the great Mike McCarthy showcased this recently as the horror it is. But no one can remember a time when even early 20th century wildlife levels would have paled in comparison to what our woods, wetlands, coasts and meadows harboured 1,000, 500, even 200 years ago.

* * *

Wildlife conservation is bigger than ever before, and we have more knowledge and insight into how to reverse population declines than any previous generation. It doesn’t have to be this way.

We need to let go of old prejudices. The Vermin Acts may have turned into legal protection for many of the species that fell victim to it, such as the raptors, martens, badgers, polecats and wildcats, but old habits die very hard (especially when you consider the illegality of killing these animals only came into force around the 80s). Persecution of these species and more continues unabated. The slaughter of eagles, harriers, peregrines and the like in the upland grouse moors is still rampant for one thing, showcasing this dated mind-set in the 21st century.

A typical example of nature ‘disneyfication’ in the 21st century. Journalist and ‘true countryman’ Robin Page struggles to accept empirical evidence that the ‘nasty’ pine martens may actually aid ‘nice’ red squirrel populations due to the conflict with his dichotomy.

The Disneyfication of nature into ‘good wildlife’ (ie. songbirds and waders) and ‘bad wildlife’ (their predators) is still prevalent. Yes, in some very specific cases I can see the place for predator control. There are some species that have pulled the short-straw on habitat loss, such as many of our breeding waders, making denuded populations extra-vulnerable to the more numerous foxes and crows. But all too often, predators are called out as a very convenient scapegoat for problems that are far more complex. Ridding the country of ‘evil’ sparrowhawks will not reverse songbird decline.

We have one of the most eroded wildlife communities in Europe, if not the world. When people talk about restoring lost species, talk often jumps straight to large predators like wolves or lynx. But there’s so many missing pieces of the puzzle before you work up to them.

We need the ‘moth snowstorms’ and other super-communities of insects that filled each summer in gluttonous number, or many of our birds face oblivion. We need the full suite of small mammals, reptiles and amphibians in abundance, that regulate ecosystems and once fed the larger mid-size predators. And in turn, we need greater diversity of the latter to maintain their balance.

There are means by which we could achieve these, if we really wanted to, but we shouldn’t give up the dream simply because it is a challenge to do so. This is a lesson even conservationists could learn, many of whom suffer from an epidemic of ‘fashionable caution’.

Yes, caution can be healthy; after all, it makes sense to think of the consequences of what might come after the adrenaline rush once you’ve jumped off the cliff. But even in my novice place in the conservation world, I have noticed how too often we scoff at the idea of many direct conservation strategies to repair the natural world, such as reintroductions or large-scale ecological restoration. Seemingly because there is either too much work, too much uncertainty, or the shifting baseline dictates that the current extirpation or remnant of a species or habitat is the best possible option.

It’s time to learn from our past to guide a spectacular future. The same should be true of attitudes whether farmer or naturalist. Both have brilliant skills that together could do so much for our natural world, if done with the right heart and mind. Many conservationists could learn from the ‘get-go’ attitude of many who work the land, while ecology should be taught in agricultural colleges as a core module rather than just a token visit from a Natural England adviser.

Don’t think that Somerset floodplains with restored reedbeds and ponds brimming with amphibian and birdlife, crafted by beavers and danced over by cranes, is a nice thought but unrealistic. Don’t suggest Norfolk meadows where each footstep is an explosion of grasshoppers and bush crickets, pierced by the calls of shrikes and skylarks, is a pipe dream. Don’t assume Devon woodlands where pine martens and wildcats hunt small mammals in the wake of wild boar trails is foolish to suggest. Don’t believe choughs and white-tailed eagles can’t soar again atop the White Cliffs of Dover – or indeed the Isle of Wight, as they did so relatively recently.

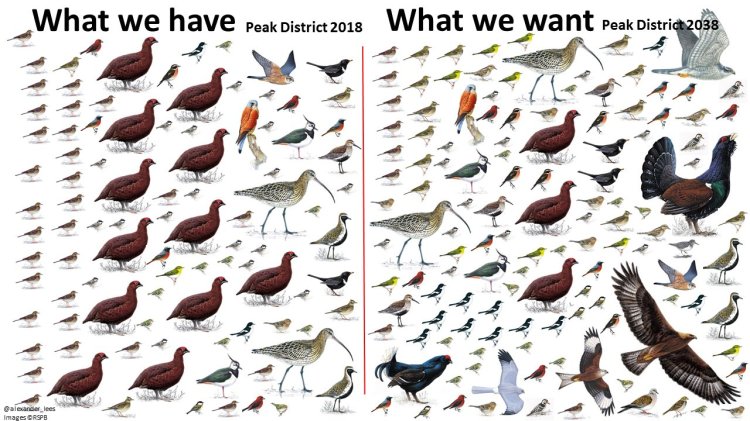

This bird rewilding proposal for the Peak District by Alex Lees recently went viral on Twitter. Exemplifying targets many conservationists are unlikely to have considered, we need more thinking like this. (Copyright Alex Lees, used with permission)

Some of these might happen through natural recolonisation, many will need a helping hand. We can’t be over-cautious in providing the latter.

Our natural history is broken. Don’t ever think that because you heard yellowhammers and saw butterflies in some nice field margins last summer, everything is fine and dandy. Otherwise the next generation will think our current state of nature is a good benchmark, and that horrifies me. But If we can realise this, it’s not too late.

Work together, work well, but most of all do rather than just talk. Because the last thing I want any future children of mine to assume, is that the natural order is to be found in silent fields.

A pine marten I photographed on the West Coast of Scotland three years ago in a front garden. There is no reason this shouldn’t take place throughout Britain.

Peter – a well thought out piece on shifting baselines, historical societal interactions with wildlife and modern day ambition seeking to reverse declines in biodiversity. One of the key points is how we wield this information (rather than using it as a blunt weapon) in seeking to work together in repairing the ‘damage’ – caused not just by control of foxes and sparrows (National Trust game lease in 1950s grouped sparrow hawk alongside crows) but also feeding the poor in urban areas (in 1854 London meat markets received 400,000 skylarks and woodcock were caught in traps on the ground) while setting a different context for puffins still harvested sustainably in the remote Faroes as are young gannets on a Scottish island as a cultural harvest monitored to prevent negative impacts on overall populations.

In 1861 the UK population (20 million) was the first in the world to exceed 50% living in urban areas. Agricultural practices were pretty ‘intensive’ with the land farmed hard with crude implements, plenty of waste, inefficient cultivation operations and plenty of diversity (livestock and cereals) to try and increase yields to feed both farmers, rural poor and increasingly hungry urban populations. Loss of diversity is the key, not intensification per say – interesting paper here https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1365-2664.12762?campaign=wolearlyview

Our population today is now 64 million (89% living in urban areas) with plenty of scope to work with those that hunt and farm (traditionally at loggerheads with that wildlife that threatens livelihood from crows on wild pheasant shoots to aphids on winter wheat) in helping the wider society try recover wildlife. As encapsulated well by the same Michael McCarthy in 2011 https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/nature/naturestudies/once-upon-a-time-in-a-land-before-pesticide-wildlife-was-so-abundant-8576870.html and demonstrated on the ground by gamekeepers working alongside scientists in mid Wales to help reinforce pine marten numbers.

I find it vaguely ironic that past hunting forests are today’s nature reserves. It’s a big journey for many. Too many grinding axes and partisan posturing is at risk of holding back progress as shifting baselines is one thing but shifting prejudices of mice and men, another!

Best, Rob

A call to arms. In simple terms, we have failed nature. It is time to put that right and cut through vested interest groups who see publically subsidised land as their own private playgrounds.

A brilliant article and I support Alex Lees rewilding idea for the Peak District and I support rewilding in general.

Nice to see environmentalists embracing more optimistic ideas for conservation, not to mention proactive ideas instead of ‘fighting back’ all the time against the cascading bad news and environmental issues.

Pingback: Rip out that hedge | Peregrine99

Good stuff. Well written Peter, with some supplementary insight from Rob.

I can’t speak for anyone else but for me, hearing statements about Puffins and Wildcats once thriving in the southwest of Britain….i don’t know how to say it, but it’s exhilarating and thrilling and it’s like experiencing fresh oxygen bursting into a stale and stifling space, and somewhere in our beings we really, really need this big big dream and we need it made apparent! The world needs the world..